March 15 2020, the day president Uhuru Kenyatta made a shock announcement to shut down schools to contain the spread of COVID 19. What followed then, had never happened in the history of the planet: Kenya joined the list of countries shutting down like dominoes all round the world culminating in nearly 1.6 billion or 93% of the world’s school going children out of school. Education systems and players struggled with the implications of a planet-wide shut down of the education systems.

By mid-April, it started becoming apparent that the shut-downs would last quite a while. The C-19 pandemic was raging wild and scientists scrambled to fully understand how to save lives. Northern Hemisphere education systems worried about exit National Examinations and how to conduct them. Many countries postponed National Examinations while a few had innovative ways of assessing exit student performance and managing transitions within the system.

Back here, the scramble to build up hospital bed capacity was on. Comparative studies began to discuss the global impact of learning losses. The term learning loss refers to any specific or general loss of knowledge and skills or to reversals in academic progress, most commonly due to extended gaps or discontinuities in a student’s education. Under the banner of learning continuity, many countries have slowly begun to use existing platforms, tools, and technologies for some form of interim learning by distance. We in the private sector turned to look at West Africa and how they managed to keep learning going during the deadly Ebola Pandemic. We struggled to find equity focussed solutions to keep learning going, ending up with the doomed Community Based Learning which was shot down by the courts.

The economic melt-down which followed the shut-down in itself jolted the country. For the private sector, this put parents and schools in opposing camps when it came to the costing of emergency learning interventions. The private education sector struggled to explain the school ecosystem and how school managements allocate finances. Schools struggled to keep their teachers employed and as a result of the inequity inherent in education during emergencies, thousands of teachers were sent home on unpaid leave. This alone would become the single issue that the private sector grappled with during the pandemic.

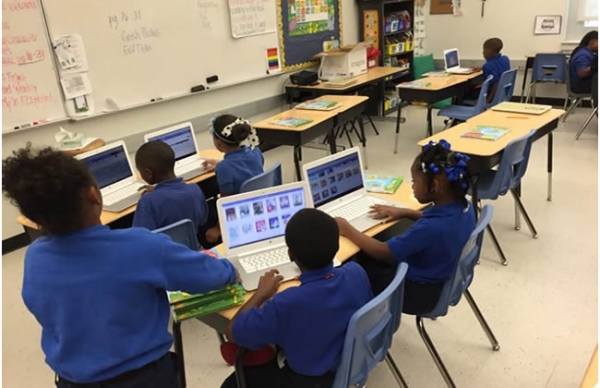

In trying to solve the problem of learning losses and to keep teachers employed, private schools rolled out online learning programmes. The International Curricula private schools stood out as thought leaders in the adoption of technology to keep learners learning. But the economic melt-down pitched parents against schools. This led to very public disagreements which affected the students’ access to education. This also eventually led to the lack of a concerted system-wide intervention for keeping education going during the pandemic.

Despite existing strategies such as KICD’s online, TV and radio lessons, the narrative had been set. Online learning was as a result relegated to the private sector, and thus the ‘zoom lessons’ -as opposed to more appropriate and preferred tech- was rolled out. In an attempt to facilitate the private schools serving the most disadvantaged the Kenya Private Schools Association set up a platform to enable schools without infrastructure to mount online learning- the Linda Mwalimu Platform. This remains the biggest innovation which attempted to put equity and access into continued learning during the pandemic.

One year down the road, what are the lessons learnt?

SEGREGATED SYSTEM

Learners with special educational needs and disabilities were the ones left out of all interventions during the pandemic. No support to parents was factored in to any of the covid interventions and as a result of the shut down of the economy, support functions such as non-emergency physiotherapy, social support etc were unavailable for these families. Interventions such as online learning simply did not factor in students with disabilities and special needs. Even as the education system reopens fully for face-to-face learning we need to acknowledge that it is hard on educators, on students and their families. Schools have to do their best to collaborate with families, think outside of the box, consider each child’s individual needs, and do their best to meet those needs in this current environment. And when best efforts don’t work, they need to circle back and fill in the gaps when it’s safe to resume in person learning.

GENDER DISPARITY

Girls’ education has been specifically challenged by the pandemic and the education emergency caused by the pandemic could roll back progress which had been made to achieve gender equality in education . According to the Global Partnership for Education “the economic security of girls is deteriorating since they have a limited source of income. The burden of household responsibility grows heavier and their freedoms may well be curtailed…” It has already been reported that there is a sharp increase in the number of girls who have not been able to return to school after the reopening of schools. The threats to girls are: increases in child marriages, teenage or early pregnancy, and gender-based violence. These threats are more visible for girls from low-income households and girls in rural areas. These barriers require targeted interventions to ensure that our gains in protecting the right to education for girls are protected.

EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS

Education during emergencies. Kenya is not a stranger to localised emergencies which affect education- force majeure events such as flooding, droughts etc, as well as instabilities which lead to insecurity. We will need a National Distance Learning Strategic Plan to ensure equity in learning during emergencies.

FLEXIBLE ENVIRONMENT

The reopening of the education system was in the end a very cumbersome process as a result of the lack of learning continuation during the shut-down. Progression mechanisms during emergencies need to be laid down. The rigidity of our curriculum as compared to other education systems negated any gains made during the pandemic. The use of Technology in Education remains a distant dream. It will need concerted system-wide efforts to ensure the competitiveness of our education system to guarantee that our students emerge as global scholars. Sections of the private education sector saw huge success in the use of technology during the pandemic. Embedding these gains and ensuring that all private schools can scale up the use of technology in schools is a challenge which has been taken very seriously. The twin roadblocks of funding and connectivity for this scaling-up process remain the main hurdles to overcome.

ADOPTABILITY TO CHANGE

Managing localised shut-downs going forward will be the challenge. Schools will have to put in strategies in place to keep learning going on despite disruptions.The recovery of learning losses will be spread out over two years. Lessons from the Ministry of Health on the resilience of young children and youth against the Covid-19 virus have helped the sector to safely reopen. Keeping teachers and other adults working with learners remains the priority for both the public and private sectors. Learning to live with the Covid-19 will continue to be a challenge, though not to the scale first envisioned. For schools, the investment in hygiene and masking should now be mainstreamed as well as an efficient and timely rollout of vaccination of teachers and other adults in schools.

SUPPORTING LEADERS

How best should school leaders be supported during the Covid and Post Covid phases?

Leadership’s impact has been made very clear during the Covid-19 crisis, in which leaders have adapted and innovated alongside teachers to ensure education continuity for children and young people. Yet leadership is often given little attention, and there has not been enough investment to understand how to best select and professionally develop leaders so they can support a wide range of education outcomes for all students.New thinking driven by strong leadership is needed if we are to create more inclusive, equitable systems that can promote quality education for every child and young person. One major finding during this crisis is the role of collaboration – among teachers, leaders, and parents – and it determined education success during this time. Education leaders need to build coalitions to create the teams necessary for providing inclusive and quality education for all – both in times of crisis and the long term. Collaboration between education leaders, teachers, and other important stakeholders – including families, civil society, health professionals and social workers, businesses, and the wider community – can enable more holistic approaches to education reforms and provide enhanced continuity and continuous improvement. This can also create opportunities for individuals such as teachers – and even those outside the education workforce – to step up as leaders at all levels of the system.When leaders create a culture of collaboration within and between schools, they can powerfully impact teachers’ professional development and leadership skills. Communities of practice and networks of schools promote sharing of knowledge, innovations, and expertise, helping teachers to lead on improving their own practice.

TRAINING AND RETAINING

The impact of the pandemic on and the implications for recruiting and retaining high quality Teachers. While enrollment in schools is steadily increasing, enrollment in teacher training programmes is falling dramatically due to requirements for higher entry criteria. And now, in the wake of a global pandemic, surveys suggest that this shortage will grow even wider. Today’s current atmosphere surrounding teaching offers a virtual approach that most educators are not well versed in, and quite frankly, would rather not deal with. Virtual learning has directly challenged the knowledge, mindsets, and skills of the teacher workforce. This, in turn, makes the pool of candidates dwindle in an already struggling predicament. For the private sector in education to retain its teachers a programme of upskilling and reskilling teachers will have to be rolled out. This is one of the areas of professional

**IMAGE** School Ecosystem

Why do teachers leave jobs?

School leaders/principals play an important role in whether teachers thrive and remain in their jobs or leave. In schools where the leader/principal provides support, and allows for teacher autonomy, and clearly communicates with teachers, teachers are then less likely to leave the profession. Culture, with an emphasis on creating a culture of inclusion and belonging, and collegiality within a school are paramount in teacher satisfaction.

Opportunities for growth and extended influence are also important to teachers’ decision to stay. Teachers want opportunities to improve their practice and take on additional responsibilities. This might include teacher leadership and instructional coaching opportunities or opportunities to attend or share at conferences.

Teachers want to feel celebrated and supported. Teachers feel unappreciated and undervalued in today’s climate so taking opportunities to elevate and celebrate successes in the community is one way to promote teacher retention.

WHAT ARE THE LESSONS FOR LEADERS FROM THE RAPID ADAPTATION TO ONLINE LEARNING?

Even before COVID-19, there was already high growth and adoption in education technology, with global edtech investments reaching US$18.66 billion in 2019 and the overall market for online education projected to reach $350 Billion by 2025. Whether it is language apps, virtual tutoring, video conferencing tools, or online learning software, there has been a significant surge in usage since COVID-19. That said, the earlier issues around the inequity inherent in online learning offerings has seen Kenya re-set back to very little use of education technologies in teaching and learning despite the advances. Learners without reliable internet access and/or technology struggle to participate in digital learning; this gap is seen across countries and between income brackets within countries. Then there are questions about how effective learning online is. The effectiveness of online learning varies amongst age groups. The general consensus on children, especially younger ones, is that a structured environment is required, because kids are more easily distracted. To get the full benefit of online learning, there needs to be a concerted effort to provide this structure and go beyond replicating a physical class/lecture through video capabilities, instead, using a range of collaboration tools and engagement methods that promote inclusion, personalization and intelligence. Here in Kenya schools have been forced to snap back and continue to focus on traditional academic skills and rote learning, rather than on skills such as critical thinking and adaptability, which will be more important for success in the future. Could the move to online learning be the catalyst to create a new, more effective method of educating students? While some worry that the hasty nature of the transition online may have hindered this goal, others plan to make e-learning part of their ‘new normal’ after experiencing the benefits first-hand.

** IMAGE** Competency

What glimpse of ‘new normal’ can the countries which have re-opened their education systems give? Schools that had invested technical and institutional capacities prior to this pandemic quickly deployed remote learning using new and old technologies and leveraging existing resources (e.g. infrastructure, devices, contents but primarily human capacities). On the flip side, schools that had limited experience with remote education have had to rapidly react by adapting external resources from partners or simply building them from scratch. Thus, while most systems swiftly transitioned to remote learning, not all started from the same position. Most schools in Kenya experienced remote education for the first time and did not have vast repositories of digital content and have faced the challenge to quickly design, implement, and sustain a distance learning programme during the covid closure. As a result, reopening schools for face to face learning was an urgent matter. Education leaders are now looking back to evaluate what can be kept going alongside the return to face-to-face learning.